One in Three Women Will Have an Abortion

Upfront disclaimer:

This article is not, in any way, making a statement for or against abortion rights. It is meant as a mathematical and statistical exercise to validate a number that has been published by various groups.

Have you heard the claim that “one in three women will have an abortion” at some point in their fertile years? If you’ve watched any U.S. political news, it is a difficult number to miss. I certainly wondered about it. I’ve heard the claim before, and I know enough statistics to check the math myself.

This statistic came about from a study by the Guttmacher Institute, which found evidence for 300.9 out of 1,000 women, based on statistical sampling. Right from the start we can see a problem. Namely, one in three (or 33.3%) is not the same as 300.9 in 1,000 (or 30.1%). The value found by Guttmacher is lower than the one in three claim. Yes, numbers matter.

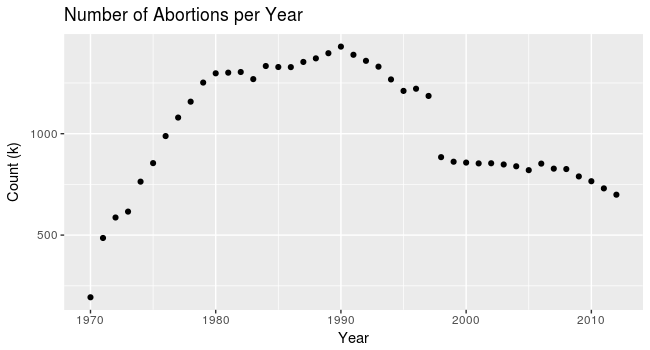

First, let’s collect some data. I do not have the ability to conduct a nationwide poll, but that is not necessary. As it turns out, medical providers are required to provide abortion numbers to the CDC. Let’s take a look at it.

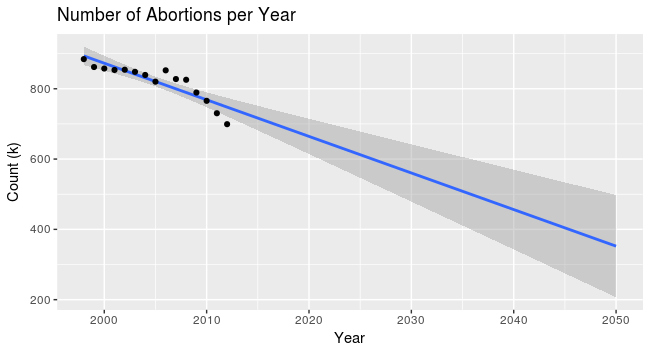

In 1990, we saw the largest number of reported abortions, at nearly 1,430,000 procedures. Since then, the number of abortions has been on a steady decline. Let’s look specifically at the years 1998 to 2012, because there is a very clear downward trend during this time that appears to be independent of the rest of the data.

We have also added a trend line and a confidence interval for future data. The confidence interval gets wider as we predict further into the future because of natural uncertainty. This model has \(R^2 = 0.7737 \). The value of \(R^2\) – the Pearson correlation coefficient – is a measure of how well the data fits the given line. In our case, a 77% fit is not bad, and it is close enough to give us some idea what we should expect to see in the future.

We can quickly perform a T test on this data set, which will give us a 95% confidence interval for the mean.

abortion.t <- t.test(abortion.data2$count)

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 791573.4 849577.8

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 820575.6

This gives us a mean of 820,576, with a 95% confidence interval between 791,573 and 849,578. If we assume this average and these confidence intervals hold steady, we can predict the likelihood that a woman will have an abortion. Let’s assume that the ages of a woman’s fertility is from 14 to 45. That is a period of 31 years. In 2015, there were an estimated 67,862,793 women between the ages of 14 and 45. We can now take advantage of the binomial distribution to determine the probability that a woman will have an abortion during this time.

lower_limit <- pbinom(0, 31, 791573 / 67862793) # Lower bound probability.

expected <- pbinom(0, 31, 820576 / 67862793) # Expected probability.

upper_limit <- pbinom(0, 31, 849578 / 67862793) # Upper bound probability.

These values represent the probability that a woman will not have an abortion during her fertile years. So, to find the probability that she will have a procedure, we subtract the value from 1, giving us the following results.

| Lower bound | Expected value | Upper bound |

|---|---|---|

| 0.3049 | 0.3142 | 0.3233 |

By these numbers, we can expect that there is 31.42% chance that a woman selected from random in the United States will have an abortion at some time during her life. Given the natural uncertainty present in the problem, we can expect, with 95% confidence that the number is between 30.49% and 32.33%.

The Obvious Problems

It should be clear that this number is too high for some circumstances and too low for others. The binomial distribution assumes that nothing changes for the duration of the analysis. This is clearly not the case. By a simple check, we can see four distinct periods in our first CDC graph. There is a dramatic increase from 1970 to 1980, a slow increase from 1980 to 1990, a slow decrease from 1990 to 1997, and a dramatic decrease from 1998 to 2012. We do not have 31 years of consistency in the past, and there is no reason to assume that we will going forward.

We would also need to know why the rate is decreasing. Are attitudes changing toward abortion? Access to birth control? Better expected health outcomes for babies? Higher incomes or improved access to social services for new moms? Are states making abortion more restrictive? Or is it a complex combination of all of these (and more) factors? These questions are important because they can tell us how much the abortion rate will change in the future.

Furthermore, our population continues to increase. If the number of abortion procedures continues to decrease and the population continues to increase, then abortion rate will fall by an even faster amount.

A better model would correct for this problem, assume that the current trend continues to decrease, continue to widen the range for uncertainty, and take into account the live birth rate which has been plummeting in this country. That would require its own detailed analysis.

Conclusion

Will one in three women have an abortion in their lifetime? By my math, no. I estimate between 30 and 32%, and I completely acknowledge that my number is high for the reasons stated above. But it is not going to be high by much – maybe a few percentage points. Either way, the message is clear. Whether one in three, three in ten, or one in four, abortion procedures are incredibly common, but they are obviously not discussed like they are. We talk about them as if they are rare. Having an abortion is roughly the same as being diagnosed with heart disease, which is the leading cause of death in the United States. Abortions are four times more common than breast cancer, 17 times more likely than deaths from influenza, 20 times more likely than suicide, 27 times more likely than a fatal car crash, and 100 times more likely than being shot. You probably know multiple who fit into these categories, and abortion is more common than all of them. (I personally know six people who have died in car crashes, three women who have had breast cancer, and two people who have committed suicide.) Whatever discussion we continue to have, we need to acknowledge that we most likely know multiple women who have had the procedure.